William H. Danforth, chancellor emeritus, trustee emeritus of Washington University, dies at 94

Led university into era of remarkable accomplishment in higher education, scholarship, clinical care

Chancellor Emeritus William H. Danforth, MD, who served as chancellor for 24 of his more than 65 years of service to Washington University in St. Louis, died Wednesday, Sept. 16, 2020, at his home in Ladue, Mo. He was 94.

Dr. Danforth, who was also an emeritus trustee, led the university into an era of remarkable accomplishment in higher education, scholarship and clinical care.

“Throughout his nearly seven decades of leadership and service, Bill forged a profound and indelible legacy that will remain in our community in perpetuity,” said Chancellor Andrew D. Martin. “Most notably, we will remember Bill for taking the university from what was once known as a commuter campus to the world-renowned institution it is today, including raising the prominence of the School of Medicine — Bill’s academic ‘home’ and the place where his leadership and service at Washington University began.

“In addition to his innumerous accomplishments, we will also remember Bill for his passion for our mission, his relentless pursuit of excellence, and his abiding appreciation for and commitment to the people who make up our Washington University community,” Martin said. “Indeed, anyone who has ever been in the presence of Bill Danforth knows how special he was and how much he cared for this place and the people who have resided, studied and worked here.”

“Anyone who has ever been in the presence of Bill Danforth knows how special he was and how much he cared for this place and the people who have resided, studied and worked here.”

Chancellor Andrew D. Martin

A private funeral will be held. The university will hold a memorial service at a later date.

During his chancellorship from 1971 to 1995, Washington University grew in national and international recognition for its teaching and research. The university strengthened its academic programs, significantly expanded resources for scholarship and scientific discovery, and completed its transition from a local college to a national research university.

By the time he retired as chancellor in 1995 and became chairman of Washington University’s Board of Trustees, his list of accomplishments included the establishment of 70 new endowed faculty professorships; construction of dozens of new buildings; tripling the number of student scholarships; and growth of the endowment to $1.72 billion endowment, which at the time was the seventh largest in the country.

“Bill Danforth was a giant in every way — leadership, character, authenticity, modesty — for the great and enduring benefit of both Washington University and the entire St. Louis region. We will forever cherish his memory,” said Andrew E. Newman, chair of Washington University’s Board of Trustees.

“Bill Danforth was a giant in every way — leadership, character, authenticity, modesty — for the great and enduring benefit of both Washington University and the entire St. Louis region. We will forever cherish his memory.”

Andrew E. Newman, chair of Washington University’s Board of Trustees

Washington University’s Hilltop Campus was renamed the Danforth Campus in 2006 in recognition of his and his family’s contributions to the university.

Strong ethical principles, the quest for improvement and concern for others defined Washington University’s 13th chancellor. Buoyed by a faith in simple virtues, he always led with the optimism that hard work and a sense of purpose could effect positive change.

His wife, the late Elizabeth (“Ibby”) Gray Danforth, was a beloved and engaged first lady. Together, they inspired and transformed the university community with their caring dedication, integrity and vision.

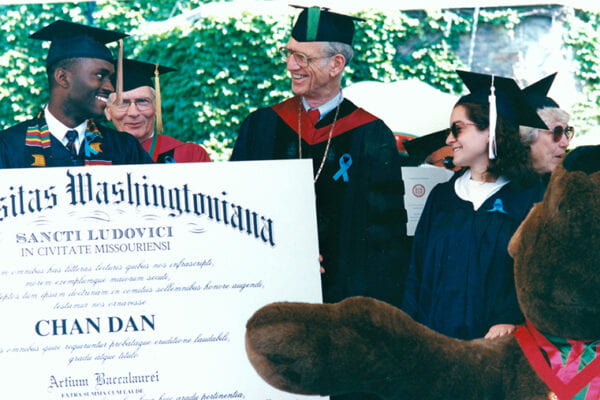

‘Uncle Bill’ and ‘Chan Dan’

To the more than 60,000 students who graduated during his chancellorship, Dr. Danforth was affectionately known as “Uncle Bill” and “Chan Dan.” He and Mrs. Danforth knew many students by name because of the countless campus events they attended and supported. He noted during one semester that he spent only two full evenings at home.

Dr. Danforth made a point of being available to students — to listen to their concerns and help them figure out a course of action. As Mrs. Danforth once said, “He never says ‘no’ to a student. All they have to do is walk into his office.”

The tradition he started in the 1970s of telling bedtime stories — everything from James Thurber to favorite family tales — to students living in the South 40 residential area endeared him to generations of alumni.

His door was also open to faculty, nearly all of whom he knew on sight and who, in turn, were well aware that they could call on him directly — and that he would patiently listen.

From cardiologist to chancellor

William Danforth was born in St. Louis on April 10, 1926, the son of Donald, a business executive, and Dorothy Danforth, and the grandson of William H. Danforth, the founder of Ralston Purina Co.

When Dr. Danforth was 12, his grandfather instructed him to literally cut the word “impossible” out of his dictionary. It was a lesson he never forgot.

He graduated from St. Louis Country Day School and spent a brief time at Westminster College in Fulton, Mo., going to school while serving in the U.S. Navy during World War II before transferring to Princeton University. He earned a bachelor’s degree in biology from Princeton in 1947.

He graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1951 and completed an internship in medicine in 1952 at Barnes Hospital, which is part of the Washington University Medical Center. After two years as a Navy doctor during the Korean War, he returned to Washington University and never left.

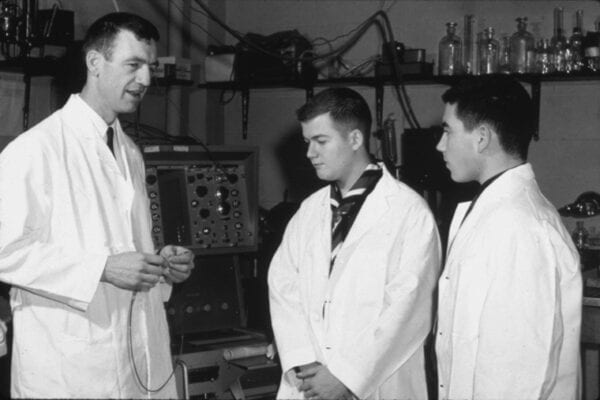

A cardiologist, he joined the School of Medicine faculty in 1957 after completing residencies in medicine and pediatrics at Barnes and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, respectively.

At age 39, he was appointed vice chancellor for medical affairs and president of the Washington University Medical Center in 1965. He was named a full professor of internal medicine in 1967.

Along the way, he did basic research in the laboratory of Nobel laureates Carl and Gerty Cori.

As vice chancellor, Dr. Danforth stood beside and gave counsel to Chancellor Thomas Eliot during the student unrest of the 1960s and was the universal choice in 1971 for 13th chancellor when Eliot retired.

When Dr. Danforth’s own father asked why he would quit medicine for the headaches of administration, he quickly replied: “Didn’t you raise us all to take on challenges?”

Leading through strength

Dr. Danforth led the university through a time of social and financial crisis, strengthening community relationships and securing important financial support.

He launched a $120 million fund drive in 1973 with a $60 million endowment challenge grant from the Danforth Foundation. When the matching goal was achieved, the chancellor noted that the money would ensure stability for long-range planning.

Numerous early milestones included the establishment in the mid-1970s of the Spencer T. Olin Fellowship Program for Women in graduate and professional studies and the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences, placing the university among a handful of schools featuring such centers.

Also established at that time was a joint Division of Biology and Biomedical Sciences, a visionary and now much-copied educational consortium of faculty affiliated with 29 basic science and clinical departments on the Danforth and Medical campuses.

Dr. Danforth continued the efforts, begun while he was vice chancellor for medical affairs, of the Washington University Medical Center Redevelopment Corp., which completed a nationally acclaimed renewal of the decaying urban neighborhoods north of the medical center, now called the Central West End.

In 1978, Dr. Danforth announced the Commission on the Future of Washington University, comprising 10 task forces chaired by trustees and each assigned to a school or major service area.

“Having wonderful, smart people was very, very important,” Dr. Danforth said in 2006 of the talented leaders he brought to the table throughout his chancellorship. “I talked with them about their ideas and always felt I was doing the right thing if I was backing the convictions of people I knew were wise.”

For 28 months, the task forces studied the university, talking in depth with its constituencies, and, in 1981, compiled a report with nearly 200 hard-hitting recommendations aimed at strengthening the university.

The commission’s work not only provided a map for the 1983-87 Alliance for Washington University campaign — which raised $630.5 million and was then the most successful university fundraising effort in the nation’s history — but also presaged Dr. Danforth’s establishment five years later of the National Councils, one for each school, the Libraries and Student Affairs, to extend the analysis, insights and dialogue.

Each chaired by a member of the Board of Trustees, the councils are made up of alumni, parents and leading national and local academic, corporate and civic leaders who bring expertise and objectivity to institutional planning.

Using the comprehensive strategic planning approach that had preceded the Alliance campaign, Dr. Danforth launched three initiatives aimed at positioning the university for the future: Project 21, the Task Force on Undergraduate Education and the University Management Team.

Dr. Danforth, through the development of these new proposals, laid the foundation for the success of the next campaign, which Chancellor Mark S. Wrighton announced publicly in 1998. The Campaign for Washington University, exceeded its original $1 billion goal, providing $1.55 billion to implement the plans.

Other highlights from the Danforth years included the formation under his leadership of the University Athletic Association, a conference for scholar-athletes; a historic university-industry research agreement with Monsanto Corp.; 20 new buildings, including John E. Simon Hall for the Olin Business School and Anheuser-Busch Hall for the School of Law; and soaring numbers of research grants, clinical breakthroughs and new initiatives. The School of Medicine, for example, was one of the few world centers selected for the Human Genome Project.

During his tenure, 10 Nobel Prizes and two Pulitzer Prizes went to people associated with the university, along with innumerable other prestigious honors. Two faculty members served as poet laureates.

Characteristically, Dr. Danforth chose a time to retire that was in the best interests of the university. Project 21 was under way, and he believed a new chancellor should be in place to oversee the plan’s final form. The day after Dr. Danforth “graduated,” as he put it, he went right back to work, as chairman of the Board of Trustees.

In 1998, Dr. Danforth helped create the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, a not-for-profit research institute with a global vision to improve the human condition internationally and regionally.

Local and national recognitions

At the 1999 Commencement, Dr. Danforth both delivered the address and received an honorary doctorate. He also became chancellor emeritus, vice chairman of the board and a Life Trustee of the university that year. He became emeritus trustee in 2019.

Among his many awards, he received the Alexander Meiklejohn Award in 2000 from the American Association of University Professors, the major professional organization for faculty, for his unflinching support of academic freedom.

The award, which is given only in years when a truly outstanding candidate is nominated, is the highest honor the AAUP bestows. Former University Chancellor Ethan A.H. Shepley received the award as well, and Washington University is the only institution to be so honored twice.

He also was named “Man of the Year” in 1977 by the St. Louis Globe-Democrat and he received the 2012 St. Louis Award for his outstanding leadership and commitment to the St. Louis region, particularly for his role in establishing the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center.

The university has recognized his and Mrs. Danforth’s commitment to the university in many ways, including the establishment in 1997 of the William H. and Elizabeth Gray Danforth Scholars Program, a scholarship for approximately 25 incoming students who embrace the Danforths’ high ideals; the naming of the William H. and Elizabeth Gray Danforth University Center in 2008; and the couple’s 1995 induction to the Washington University Sports Hall of Fame for their dedicated support and revitalization of the university’s athletic programs.

Survivors include two daughters, Maebelle Anne Danforth of St. Louis County and Elizabeth G. Danforth of Ladue, Mo.; a son, David Danforth (Tina) of Clayton, Mo.; a brother, former U.S. Sen. John C. Danforth; 13 grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren. A fourth child, Cynthia Danforth Prather, died in 2017.

In addition to Ibby, his wife of 54 years, Dr. Danforth was also preceded in death by his brother Donald Jr. and sister, Dorothy Danforth Miller.

He had noted many times that he considered his greatest achievement was the nearly 60,000 students who graduated during his tenure.

When asked once by a young alumnus what would he like to be most remembered for, Dr. Danforth replied “for you. That’s what I would most like to be remembered for — the lives of the young people who have gone to Washington University during my time as chancellor.”